THE

VILLA ROMANA DEL CASALE

As the coach effortlessly wove its

way in a continuing downward spiral, my view of the terracotta roof tiles of

the houses in the village below was replaced by an army of tall, regimented

trees. On passing these the driver entered the coach park, parked his vehicle

alongside another and silenced its engine. When stepping out of the coach, my

eyes instinctively rejected the bright, early morning light of the sun but, as

I armed myself with sunglasses, my body soaked up its warming rays. As I

impatiently made my way towards the villa’s entrance my eyes glimpsed, to the

right and the left, men and women beginning to set out their stalls from which

visitors to the villa would be able to purchase numerous items of memorabilia,

including guide books written in a number of different languages.

|

| Aerial picture of Villa Romana Del Casale |

The villa is to be found nestled at the foot

of Mount Mangone in the valley of the River Gela, which is populated with trees

of pines, elms, poplars and hazels, about three kilometres south west of Piazza

Amerina, a province of Enna, in Sicily. Archaeology suggests that this early 4th

century villa was a later addition to an earlier villa which was built between

the 1st century and the second half of the 3rd century

AD. The catalyst for the building of the villa was stimulated when, in late

antiquity, Sicily’s Roman rulers partitioned most of its hinterland into huge

agricultural estates, called ‘latifundia’, known in the singular as

‘latifundium’. The size of this building, with many of its rooms containing

high quality mosaic floors and wall-paintings, suggest that this was probably

the centre of such a latifundium and was also the residence of a wealthy man

and his family, he possibly being a member of the Senatorial class. It is

likely that this latifundium’s main function was to produce grain which would

have been transported to Rome. But the villa itself, as well as being a

residence, could have functioned as a centre of political and administrative

power for the territories in which it resided.

The villa is a single storey building

composed along three terraces at the foot of the hill and was built around

three different axes. The first terrace lies to the east, bounded by an

aqueduct which was supplied with water from the River Gela, which would then

have drained into a raised tank. From here lead pipes divided up to feed water

to various rooms in the villa. This terrace also contained the basilica and

some private apartments, including the 60 metre long corridor of the Great

Hunting Gallery. From here one could move to the second terrace, which was

centred on a rectangular peristyle courtyard, which also included a triclinium

complex with an oval courtyard. Both could be accessed from the corridor of the

Great Hunting Gallery. The third terrace contained the baths and the monumental

entrance to the villa marked by a tripartite niched arch. The villa complex is

more than 550 metres above sea level and covers an area of 8.92 hectares (22.0

acres).

THE

DEMISE OF THE VILLA

Sicily’s

strategic location, in the centre of the Mediterranean Sea, and separated from

the Italian mainland by the Strait of Messina, made the Island a crossroads of

history, for it became a pawn of conquest and Empire.

By 440

AD, Sicily had been invaded by the Germanic tribe/s, known as ‘The Vandals’,

who were commanded by King Genseric. In time, these warriors would have

stumbled across the Roman villa and would have plundered it. Fortunately, it

seems, that the mosaics and the villa’s frescoes remained secure and undamaged.

The

Vandals followed a type of Christianity known as ‘Arianism’ which the Romans

considered to be heretical. Consequently the Vandals began to persecute members

of the catholic clergy. Although, in all probability, daily life in the rural

areas would have been unaffected.

The

next invaders, after the Ostrogoth’s, to wear the robes of rule in Sicily were

the Byzantines. The ‘General’ Belisarius secured the island for his Emperor

Justinian I.

The villa would possibly have become, by

now, part of a rural settlement which was fortified and modified. The perimeter

walls were thickened and the aqueduct which supplied the bath-house with water

was terminated. The frigidarium within the villa’s bath-house was converted

into a place for Christian worship. Archaeology seems to suggest that during

the Arab and Norman rule of Sicily the villa was divided into many different

living spaces and areas for productive activity. It had evolved as part of a larger

medieval settlement. Sadly, sometime during the second half of the 12th

century a huge landslide, from the nearby Mount Mangone, buried the complex

under tons of mud and foliage many metres deep. But, a new, thriving

agricultural settlement began to be established nearer the city of Piazza which

carried the name of Casale. As the years tumbled away, the villa would have

faded from memory until it was completely forgotten.

THE REAWAKENING OF THE VILLA

Local

farmers, with weather beaten faces, strong muscly backs and well-worn arms and

hands, were instrumental in discovering where the Roman villa’s remains were

buried. During their daily toils in the fields of the Gela River valley, at the

foot of Mount Mangone, their ploughs struck the standing remains of some walls.

This inspired the beginning of the resurrection of the villa from its tomb of

numerous alluvial layers full of debris. As the word spread about the discovery

of the walls, illicit digs by treasure hunters, hoping to find treasure of

monetary value, began in the area. It is possible that damage was done to some

of the mosaics during these clandestine excavations.

In 1820, a

gentleman by the name of Sabatino Del Muto, on behalf of Roberto Fagan, the

British Consul-General in Sicily, performed the first authorised excavation on

the site. These early excavations threw up ideas, to the academics of the day,

that the site may be the remains of an ancient temple. This theory was laid to

rest when, during the 1881 excavations, in the central space of the triclinium,

an area now known as ‘The Twelve Labours of Hercules’, was revealed. As these

excavations proceeded nearby, a square pavement made of white marble slabs

arranged in a circle was noticed. Also found were glass tesserae, in various

colours, some of which had a gold or silver glaze. The archaeologists concluded

that these tesserae must have covered the internal wall of a now destroyed

(Basilica) building. Between 1929 and 1955 most of the shroud protecting the

villa had been removed, revealing approximately 3500sq metres of mosaic floors.

Further work between 1955 and 1963 targeted conservation projects in some of

the rooms and the villa’s colonnades. Excavations during the 1970s helped to

give more clarity to the chronology of the complex, while further campaigns

between 1983 and 1988 yielded results concerning the succession of stratigraphy,

plus recognition of structures relating to the early-first century AD roman

villa. In 2004 part of the medieval habitation built on top of the later villa

was discovered to the south.

Interestingly, during the 1929 excavations, on

a parcel of land behind the villa and close to Mount Mangone, a late Byzantine

necropolis was unearthed. This cemetery yielded an estimated one hundred

graves, although many had been destroyed by farming activities and emptied of

their funerary goods. The tombs were rectangular in shape and their insides

were lined with rocks. The tombs were then sealed using sheets of local stone.

A collection of grave goods were noticed, recorded and then retrieved. These

were numerous small uncoloured earthenware, single-handle pitchers. All had

been placed to the right and left of the skull of the deceased. The most

interesting find was a small African Samian ware decorated flask.

THE VILLA TODAY

What

awaits to welcome our eyes within the villa and its complex today, is the

remains of what was possible to achieve in the Roman Imperial Age. Education

and great wealth combined together to entice artists, craftsman, architects and

engineers to create, with unparalleled splendour, a visual history of social

practices and fashions of the late Roman aristocrats.

The outer

shell of the villa, its walls, were built using locally sourced limestone and

sandstone blocks. The ceilings were constructed with wood, and were possibly

decorated, while terracotta tiles were used for the roofing. Pillars of marble,

creating an atmosphere of opulence and style, were imported from North Africa

and can be distinguished by colour. 90% of the marble used to decorate the

Basilica came from Egypt. Also within the Basilica, some intense blue coloured

lapis lazuli gemstone tesserae were discovered. This expensive material could

have originated from the Jar-E-Sang mine deposits found in north east Afghanistan.

In the frigidarium glass tesserae were excavated which were probably used as

facing for its ceiling and for some parts of its walls.

The red and purple marble was known as

porphyry, sourced from the Arabian region in Egypt, while other marble came

from Italy, Greece, Africa (Libya) and Asia Minor. Within the villa there is a

large range of marble veneers and two types have been recognised, lumachella

from Egypt and madreponte rossa from Asia Minor.

The mosaicists who laid the floors were

Carthaginians. Usually the geometrical mosaics were prepared in advance, within

workshops that were close to the villa. Here they probably used templates for

reoccurring patterns. The figurative mosaics were constructed on site using

marble tesserae of an array of colours and shades. Perhaps the geometrical

patterns were used to decorate the service rooms, while figurative mosaics

decorated the private and more important rooms.

TOUR OF THE VILLA

KEY

1. ENTRANCE

2. POLYGONAL COURTYARD

3. LARGE LATRINES

4. SHRINE OF VENUS

5. BATH VESTIBLE

6. GYMNASIUM-PALESTRA

7. PRAEFURNIUM

8. CALDARIUM

2. POLYGONAL COURTYARD

3. LARGE LATRINES

4. SHRINE OF VENUS

5. BATH VESTIBLE

6. GYMNASIUM-PALESTRA

7. PRAEFURNIUM

8. CALDARIUM

9. TEPIDARIUM

10. MASSAGE ROOM

11. FRIGIDARIUM

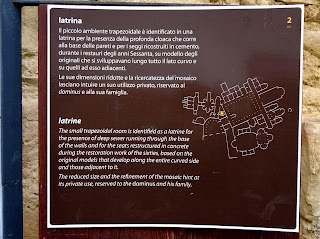

12. PRIVATE LATRINE

10. MASSAGE ROOM

11. FRIGIDARIUM

12. PRIVATE LATRINE

13. VESTIBULE OF ADENVENTUS

14. SHRINE OF THE HOUSEHOLD GODS

14. SHRINE OF THE HOUSEHOLD GODS

15. QUADRANGULAR PERISTYLE

16. GARDEN AND FOUNTAIN

16. GARDEN AND FOUNTAIN

17. PRIVATE ENTRANCE TO THE BATHS

18. ROOM CONTAINING A KILN

18. ROOM CONTAINING A KILN

19. INNER SERVICE ROOM

20. THE KITCHEN

21. FOURTH SERVICE ROOM

20. THE KITCHEN

21. FOURTH SERVICE ROOM

22. RAPE OF THE SABINE WOMEN

23. ROOM OF THE LOST MOSAIC

23. ROOM OF THE LOST MOSAIC

24. ROOM OF THE FOUR SEASONS

25. ROOM OF THE FISHING CUPIDS

25. ROOM OF THE FISHING CUPIDS

26. ROOM OF THE SMALL HUNT

27. ROOM OF THE OCTAGON MOSAIC

27. ROOM OF THE OCTAGON MOSAIC

28. ROOM OF THE CHEQUERED MOSAIC

29. CORRIDOR OF THE GREAT HUNT

29. CORRIDOR OF THE GREAT HUNT

30. ROOM OF THE PANELLED MOSAIC

31. ROOM OF THE BIKINI GIRLS

31. ROOM OF THE BIKINI GIRLS

32. DIAETA OF ORPHEUS

3. THE SMALL COURT

3. THE SMALL COURT

34. CORRIDOR LINKING THE SQUARE PERISTYLE AND XYSTUS

35. THE KITCHEN

35. THE KITCHEN

36. ROOMS OF THE GRAPE-HARVESTING CUPIDS

37. THE ELLIPTICAL PERISTYLE (XYSTUS)

37. THE ELLIPTICAL PERISTYLE (XYSTUS)

38. ROOMS OF THE FISHING CUPIDS

39. THE TRIPLE-APSED TRICLINIUM

39. THE TRIPLE-APSED TRICLINIUM

40. EASTERN AQUEDUCT

41. HALL OF ARION

42. ATRIUM OF THE FISHING CUPIDS

41. HALL OF ARION

42. ATRIUM OF THE FISHING CUPIDS

43. CUBICLE OF MUSICIANS AND ACTORS

44. VESTIBULE OF THE SMALL CIRCUS

44. VESTIBULE OF THE SMALL CIRCUS

45. VESTIBULE OF EROS AND PAN

46. CUBICLE OF THE CHILDREN HUNTING

46. CUBICLE OF THE CHILDREN HUNTING

47. THE OCTAGONAL LATRINE

48. THE GREAT BASILICA

49. VESTIBULE OF POLYPHEMUS

48. THE GREAT BASILICA

49. VESTIBULE OF POLYPHEMUS

50. CUBICLE OF THE FRUIT MOSAIC

51. CUBICLE OF THE EROTIC MOSAIC.

51. CUBICLE OF THE EROTIC MOSAIC.

The

monumental entrance to the villa is to the south. This imposing masonry

structure, reinforced at its ends by squared stones, supported a three arched

opening. The central one is the largest measuring 4.5 metres. These entrances

were flanked by marble columns. At the base of the central pillars are four

basins, all with their insides lined by simple white mosaics, which would have

functioned as small fountains.

The two outer ones are rectangular and the two

inner ones are shell-shaped. These fountains in antiquity would have been

dedicated to minor female divinities (Nymphs) who embodied authentic forces of

nature.

The four fountains were, perhaps, symbolically represented by the following; Nereids, the female spirits of seawaters; Naiads, the nymphs of rivers, streams and lakes; Dryads, the spirits of the forests; and the Hamadryads, who inhabited a particular single tree. On some parts of the fountains are mosaics with frescoes depicting foliage of flowering branches with birds showing an interest. Black, off white, grey and red coloured tesserae are noticed.

|

| INSIDE OF ENTRANCE WALL |

The four fountains were, perhaps, symbolically represented by the following; Nereids, the female spirits of seawaters; Naiads, the nymphs of rivers, streams and lakes; Dryads, the spirits of the forests; and the Hamadryads, who inhabited a particular single tree. On some parts of the fountains are mosaics with frescoes depicting foliage of flowering branches with birds showing an interest. Black, off white, grey and red coloured tesserae are noticed.

|

| FRESCOS ON ENTRANCE WALL |

A keen

eye can pick out some of the frescos which have survived to this day, for to

the right, on the long wall, horses’ hooves are still visible. And on the

façade of the entrance, to the right, is a military banner with four golden

heads representing the four emperors of the Tetrarchy. This was a system of

government instituted by the emperor Diocletian in 293AD, which was to continue

until 313AD.

During that period, it helped to end the crisis of the 3rd

century and generate the recovery of the empire. The four Tetrarchs were based

in cities close to the empire’s frontiers and would have defended it from its

bordering rivals. The four capitals were Nicomedia, which is modern Izmit in

Turkey; Sirmuim in the Vojvodina region of modern Serbia; Mediolanum, now known

as Milan, and Augusta Treverorum, now called Trier in Germany. By 313AD

Constantine controlled the western half of the empire while Licinius controlled

the east. But by 324AD Constantine had defeated Licinius and reunited the two

halves of the Roman Empire.

THE

POLYGONAL COURTYARD (2)

Just beyond the shell-shaped fountains our

eyes are greeted by a polygonal-shaped courtyard. This courtyard was framed by

a portico with eleven marble columns with ionic capitals. These capitals would

have been characterised by the use of volutes (spiral scrolls) and egg and dart

moulding (Greek). In the middle of the courtyard, which was paved with

sandstone, was a square fountain, which would have collected rainwater which

was then conveyed to the nearby large latrine. The ornamental tiling of the

portico, which carried a multi-coloured geometric design, has all but

disappeared.

THE

LARGE LATRINES (3)

Access to the large latrines is through a

small foyer, where a small portion of a black and white checkerboard mosaic has

survived, which then opens up to a once sheltered semi-circular portico, which

would have been supported by brick columns. The individual toilets were marble

basins. The latrines mosaic ornamental tiling, of which a little is still

visible today, was surrounded by a channel of constantly flowing water which

then removed human waste away from this area. It would have eventually discharged

into the River Gela. Curtains, individually hanging between the columns, would

have generated a limited amount of privacy. These toilets were used by servants

of the villa and visitors to the bath-house. In all probability, the resident

family and invited guests used the latrines situated near to the Basilica.

|

| MOSAIC FROM THE ENTRANCE |

SHRINE OF VENUS (4)

This small room was possibly a shrine

dedicated to the Goddess Venus, for parts of her statue were found here. She

was the Roman Goddess of love, sex, and fertility whose Greek counterpart in

mythology was Aphrodite. Also, this room would have served as the servants’

entrance to the bath complex.

Its mosaic floor is a colourful and skilful creation,

containing a geometric design of squares and diamonds. If one’s eye is focused

onto their black and white banded borders, the whole floor binds together,

seemingly, in an up and down, and side to side fashion. The centres of the squares

and diamonds each contain their own individual artistic design.

|

| NOTICE THE MODERN REPAIR AT THE TOP |

THE BATHS VESTIBLE (5)

This is a square room with frescoed

walls and a stunning geometric designed mosaic floor. It brings together high

quality artistic design, which was then brought to life by the craftsmanship of

a master mosaicist.

The tesserae are small, but neatly laid, and his choice of

colours blend well together. Grey/white and red/white guilloche binds the whole

design together. The oval designs hold in their centres two fish, face to face.

Their heads are black as are their small tail fins. They are completely

surrounded by a wave design in red. The large concave square holds more of the

same in diminishing sizes.

THE GYMNASIUM – PALESTRA (6)

This rectangular room with two apses and

walls adorned by frescoes is dressed with much to view. The multi-coloured

mosaics depict the Circus Maximus in Rome, where chariot races were held in

honour of Ceres, the Goddess of agriculture and grain crops. In Rome the Circus

Maximus was oblong in shape and split in two by a barrier (spine) that ran down

the middle of the track. It was 621 metres (2037ft) in length and 118 metres

(387ft) in width. Its circumference was one mile.

The chariot races were between four

factions who owned and managed the horses and could be identified by different colours

worn by the charioteers - green (Prasina), white (Albata), blue (Veneta) and

red (Russata). Within this room at the villa, a number of shields holding these

colours are displayed on sections of the floor close to the walls.

The central spine that would have divided

the arena is depicted here with such precision that much is recognised that

would have been on show at the Circus Maximus in Rome. At its centre is the

obelisk 40.4 metres (132ft) high, which was brought to Rome from Egypt in 10 BC

by the then Emperor Augustus. Also seen here is a tower (Phala) surrounded by

columns, from where important guests would have gained a better view of the

competing chariots. On its top perched the winged Nike, the Goddess who

personified victory. There seems to be a bronze column at each end of the

spine, and further on, my inquisitive eyes pick out a statue of the Goddess

Cybele, the mistress of wild nature, on the back of a lion. Close by is the lap

counter, a hanging line of sculpted marble eggs. These eggs were symbolic to

Caster and Pollux, the divine patrons of the horse, for both were born from an

egg. As each lap passed an egg was lowered.

Mosaics on either side of the southern

entrance show groups of spectators and amongst the crowd two young boys offer

them, from their trays, flat bread/buns. At the Circus Maximus in Rome 150,000 people

could be accommodated within its three tier stadium. The first tier was

constructed with stone and the other two were of wood.

Here, a boy, holding a long bolt in his

hand, opens the gates (carceces) from which the chariots of the four factions

would emerge, each being drawn by four horses with their heads decorated by a

sprig of foliage and their tales plaited. The winning chariot seems to be from

the Prasina faction, as the charioteer is dressed in a short green tunic. The

palm of victory would have been presented to him by the Magistrate who is

dressed in a richly coloured trimmed gown. Next to him is the judge (Tybicen)

who, with his cheeks puffed out, is sounding a long tuba, which ends the

competition. He looks rather grand wearing his official hat and red/black tunic

which is held together by a brooch on his right shoulder.

Symbolically, this depiction of the

Circus Maximus within this gymnasium, perhaps relates to the belief that the

charioteers would have spent much time building up their muscles and fitness

levels to able to compete successfully at these events.

Many

scenarios seep into my head as to what manner this gym would have been used in

Antiquity. For instance, were the young men here traditionalists and, like the

Greeks, would have performed their efforts in the nude? And did they work to a

specific routine of exercise? Also, were the walls lined with benches so an

older generation of men could observe and meet up to talk politics and discuss

philosophy? As I begin to smell the sweat, I decide to dismiss these thoughts

from my mind, remove my aging eyes from this gymnasium and move on.

THE PRAEFURNIUM (7)

Here

are the remains of the three furnaces where fires were lit to produce enough

heat for warming air and water, which would then be channelled through terracotta

pipes to the Caldarium. The outer walls of the furnaces were lined with

terracotta tubila, which protected the walls and helped to prevent heat loss.

THE CALDARIUM (8)

This hot room was divided into three

areas, so both men and women could bathe here. The rectangular bath tub to the

left hand side was used by the men, and the tub at the right hand side was

assigned for women.

Both tubs were supplied with hot water fed by pipes from the tanks upon the top of the furnaces. The central part of this room featured a raised floor that was supported by pillars of individual terracotta tiles (pilae). Hot air circulated along the pillars and then up the tubules in the walls (hypocaust) which created a sauna atmosphere. The room’s inner heat was regulated by two windows assisted, perhaps, by valves placed in the roof. All could be opened or closed to help maintain a constant temperature.

Both tubs were supplied with hot water fed by pipes from the tanks upon the top of the furnaces. The central part of this room featured a raised floor that was supported by pillars of individual terracotta tiles (pilae). Hot air circulated along the pillars and then up the tubules in the walls (hypocaust) which created a sauna atmosphere. The room’s inner heat was regulated by two windows assisted, perhaps, by valves placed in the roof. All could be opened or closed to help maintain a constant temperature.

This was a long room with both of its ends

stylized by a semi-circular apse. A hypocaust was also noted and the room

operated as a sauna. Hot air produced by the furnaces was regulated by two

chimneys placed outside the two apses.

The mosaic floor was 20cm thick and was

supported by 80cm high cotto brick columns. Sadly, most of the mosaics in this

room have not survived, although the few fragments that remain possibly refer

to a scene from the race of the torches (lampadedromia). This story originates

from Greek mythology when in ancient times the Olympic Games was started with a

torch race. The first athlete to arrive at the designated temple, such as the

one dedicated to Prometheus, a Titan who stole fire from Mount Olympus and gave

it to mankind, would gain the honour of lighting the official flame to start

the games.

Eight

brick pillars situated along the sides of this Tepidarium would have supported

a barrel shaped roof, and consequently the condensation would run down this,

rather than drip on to the bathers below.

It was prudent, on occasions, to wear

sandals which had wooden soles to combat the heat of this floor.

The Tepidarium was a place for

socializing and perhaps to conclude business deals. Also to make social plans

and on occasions to find an audience for political speeches.

THE MASSAGE ROOM (10)

This small room abuts the Tepidarium and

contains a faded framed mosaic which shows signs of an attempted repair,

possibly carried out during the Byzantine period. Five male figures are

presented to us, of which four are possibly slaves. In the top part of the

mosaic one slave seems to be giving a massage to the second figure, while the

third has at his disposal the ‘tools’ of the massage room. He has in his right

hand an ampoule, which hangs from a strap, which would contain aromatic oils,

and a strigil. The perfumed oils were applied to the skin and then scraped off,

along with any sweat and dirt, by the strigil, a metal instrument with a curved

blade.

Below them are two more slaves, each with their names written upon their

loincloths, Titus and Cassius. Cassius was probably born in Syria, betrayed by

his cone-shaped hat. Titus possibly cleaned the strigil with the water in the

bucket, which he carries in his right hand, while Cassius would mop up any

spilt water and other mess. Part of the mosaic showing the long handle of the

mop has been lost.

THE FRIGIDARIUM (11)

On entering this huge octagonal-shaped

room, my mind’s eye is immediately entrusted with its past magnificence. In

antiquity the art work under my feet would have been glorified by wall frescoes

and a decorated ceiling. Its supporting marble columns, with their flowing pale

colours, would have given the Frigidarium the presence of subdued royalty.

This room was embellished with six

recesses, two contained cold water baths, while the other four were changing

areas equipped with benches where bathers could deposit their clothes. It was

possible that slaves could be hired to keep ones belongings safe.

The central room holds an imaginative

visual creation boosted by a tapestry of numerous and integrating colours.

Within the mosaic’s centre is an incomplete circle of four narrow boats. Each has

a figure head at the front and a curving tail at the rear. All of the boats

contain two cupids, rowing and fishing. Many species of fish swim around the

boats as do sea-lions, dolphins and octopuses. All of these natural beings are

joined in the sea by mythological creatures including Nereids, the female spirits

of the seawater. Tritons are also present; their upper bodies are of human form

while their lower bodies are of fish. A Centaur is noticed, being half human

and half horse. It commanded human intelligence and speech. There is also a

place for a Hippocampus, with the upper body of a horse and lower body of a

fish.

Two of the recesses still retain nearly

intact bath-house scenes. One focuses on a man and the other on a woman. The

man is portrayed seated on a leopard-skin stool, with his right hand he holds

together what seems like a dressing gown. Sadly, his left hand is lost. His

servant on his right holds what seems like a towel, after just finishing drying

his master’s back. The servant on his left holds in readiness, on a tray, the

rest of his clothes.

The other scene, framed in a semicircle, illustrates a

pensive looking woman being sensitively aided to undress by two handmaids. As I

reflect on these two mosaics, my mind conjures up a thought that the man could

be an official of high office, a person of status and wealth. He sits on an

expensive leopard-skin cushion and his bathrobe looks chunky but stylish. Also

his two servants wear similar shoulder panels and their tunics are of quality-looking

fabrics.

|

| MARBLE VENEER |

THE PRIVATE LATRINE (12)

This semi-circular room was accessed at

the foot of a short flight of stairs. In Antiquity this room had a door which

would have guaranteed privacy. Opposite the three marble toilets there seems to

have been a marble wash basin; above it is a hole, suggesting that running

water was available for personal hygiene. To occupy one’s eyes while busy, is a

mosaic floor which contains within a black border five animals. These animals,

a leopard, ass, hare, partridge and a great bustard are seemingly engaged in a

game of chase.

Beneath the toilets was the sewer which

flowed with water, removing all the waste down a westward gradient and away from

the villa.

|

| FRESCOS ON THE TOILET WALLS |

THE VESTIBULE OF THE

ADENVENTUS (13)

This rectangular room stimulates

interest and much intrigue, even though most of its mosaic floor has been lost

to the ravages of time. It is possible that it had multiple functions. As well

as being a place to greet and welcome important guests, there are indications

that perhaps on occasions it may have been used for a place of worship.

The

outer part of the mosaic, known as the mat, contains a geometric diamond

pattern and all of the boxes, when looked at with inquisitive eyes, reveal

small white crosses. The figurative creation within this mosaic is seemingly

surrounded by a continuing line of red tesserae in a dentil design.

When viewed, we see a figure holding in his right hand a candelabra. He gives the impression, by his quality and elegant attire, of being of regal status, or at least a master of ceremonies. The person standing behind him and wearing a tunic is probably a servant, as all the other figures seem to have their heads decorated with laurel leaves. In the bottom half of the mosaic a figure grips a book, possibly a prayer book? Perhaps, then, this mosaic depicts a service of worship? Returning to the top of this figurative piece, two small branches of olive leaves are seen - the olive leaves being the classical symbolism of peace and the laurel of divine love.

When viewed, we see a figure holding in his right hand a candelabra. He gives the impression, by his quality and elegant attire, of being of regal status, or at least a master of ceremonies. The person standing behind him and wearing a tunic is probably a servant, as all the other figures seem to have their heads decorated with laurel leaves. In the bottom half of the mosaic a figure grips a book, possibly a prayer book? Perhaps, then, this mosaic depicts a service of worship? Returning to the top of this figurative piece, two small branches of olive leaves are seen - the olive leaves being the classical symbolism of peace and the laurel of divine love.

This small apsidal is in the south-west

corner and to the right of the peristyle’s frontal portico. It is a rectangular

room flanked by two columns which would have helped to support the shrine. The

shrine is floored with an eight sided star geometric mosaic which is supported

by a number of diamond and square lozenges with motifs in their centres. The

centre of the mosaic holds a laurel wreath which in turn contains an ivy leaf.

The laurel and ivy symbolise perennial life and immortality. This shrine would

have imparted an atmosphere of intimacy between the living and their departed

family members. Within it the good spirits of the dead would be worshipped to encourage

from them a blessing for the family’s prosperity. This activity was known as

the Worship of the Lares. The origin of this worship can be traced back to the

fact that, until it was forbidden by the Laws of the Twelve Tables (449 BC),

the Romans buried their dead in their own houses. Within the shrine there would

have been a small altar which would have held statues of the household divinities.

The peristyle measured 38m by 18m and

was surrounded by 32 slender fluted columns probably sourced from eastern

Greece. All were topped with Corinthian capitals decorated with acanthus leaves

and scrolls. These columns were all connected by a low marble-covered wall.

Seemingly, on either side of all the columns were sculptured marble dolphins.

To the south side, along its main wall are the remains of some frescos showing

a procession of armed figures carrying large shields.

This peristyle is surrounded by a

continuing corridor of 162 square mosaic panels. All of which are bound

together by a never ending frame of multi-coloured guilloche. The centres of

the individual squares present a shield like effect with four straps binding

the laurel wreaths in place. Featured within the laurel wreaths, and enclosed

by a circle of black/grey tesserae, are animal heads of wild and domestic

natures.

The laurel wreaths themselves are bounded by a similar circle while

the four corners of the squares are shared by ivy leaves with tendrils and

varying species of birds. The laurel wreaths diversify alternately from dark to

light in their composition.

|

| ROMAN GENERAL GOVERNOR OF DIOCESE OF AFRICA? |

Inside the peristyle was a garden furnished

with a three-basin fountain which had an east-west orientation. It consisted of

two semi-circular basins, one at each end, with a wider circular one in the

middle which contained the fountain. The fountain received its water via an

eastern aqueduct. The pools’ bottoms, sides and borders were dressed with a

geometric mosaic.

I imagine that, like the mosaics, the

garden was designed and presented in such a way to promote a positive impact on

serenity for the mind and seduce, by an array of colours at all times of the

year, the viewers’ eyes. History reveals that a roman garden could have been an

amalgamation of some of the following: cypress, rosemary, mulberry trees and a

variety of smaller dwarf trees. Extra colours could have been generated by

roses, violets, marigolds, cassia, narcissi and hyacinths. Perhaps small paved

paths would have invited peaceful strolls around the garden.

The peristyle had a positive impact in

allowing light to penetrate the adjoining rooms and its garden was a meeting

place for cordial encounters.

The villa’s family and their guests would

have gained entry to the baths through this room. The room itself presents a

figurative mosaic harbouring the suggestion that it represents the mother of

the villa’s family accompanying two of her children to the baths. The ‘hostess,’

the central figure of the five, demands my attention with her fashionable

stylized hair, earrings, sophisticated

necklace and her long sweeping gown with its wide sleeves. Her face,

seemingly, is about to break into a smile as she affectionately places her left

hand upon her child’s shoulder. The other young person, to her right, seems to

be holding on to mother’s arm which is obscured by the mother’s luxurious gown.

To the far right and left are two maids.

The one on left holds an open basket containing clothes to be worn after the visit to the baths. The other maid, in her right hand, holds the straps of a box which possibly contains oils to be used on the family’s bodies when the bathing has finished. This maid also possesses a red shoulder bag in which, perhaps, the family’s personal items of jewellery are kept safe while they are bathing. Both of the children seem to be wearing warm cloaks over their tunics, while their mother wears a stola beneath her gown.

This mosaic is framed within three bands of black tesserae and also

noticed is a high backed armchair with an urn close by. The hand of the

mosaicist shows much skill by defining the folds within the figures’ garments

and the shadows at their feet. The whole scene is elegant and dignified. It is

so sad that the wall art has all but disappeared.

The one on left holds an open basket containing clothes to be worn after the visit to the baths. The other maid, in her right hand, holds the straps of a box which possibly contains oils to be used on the family’s bodies when the bathing has finished. This maid also possesses a red shoulder bag in which, perhaps, the family’s personal items of jewellery are kept safe while they are bathing. Both of the children seem to be wearing warm cloaks over their tunics, while their mother wears a stola beneath her gown.

This service room was entered via the peristyle, next to the door which

gave entry to the baths. It holds a geometric mosaic which in parts is fairly

well preserved.

Unfortunately, in one corner a kiln was built during the Arab or Norman era, which destroyed that part of the mosaic. The mosaic as seen today contains crosses formed by intertwined guilloche and circles of light and dark tesserae. All of these circles have a circular band of white tesserae and at their centres have varying styles of motifs. The lozenges all hold the same styled motifs and all of the designs interconnect.

Unfortunately, in one corner a kiln was built during the Arab or Norman era, which destroyed that part of the mosaic. The mosaic as seen today contains crosses formed by intertwined guilloche and circles of light and dark tesserae. All of these circles have a circular band of white tesserae and at their centres have varying styles of motifs. The lozenges all hold the same styled motifs and all of the designs interconnect.

INNER SERVICE ROOM (19)

This room, behind the first, was also used

by service personnel and was floored by an intricate and eye absorbing geometric

mosaic, displaying in red, white and dark green/black tesserae, stars, squares

and hexagons.

Here we see hexagons holding a six pointed

star which in turn contains six petal stylised flowers. The outer tips of the

hexagons touch a four pointed star that encloses a square containing a Solomon

knot. There are numerous squares that blend into the overall design and all

have their own varying individual motifs.

THE

KITCHEN (20)

This rectangular shaped room did not possess

a mosaic, only a floor covered in lime mortar mixed with crushed pottery. It

seemed to have contained a masonry tank with a lead wastewater runoff pipe and

a raised bed for hot coals used for cooking.

This service room is situated next to the

first service room and could be entered from the peristyle. Nearly half of its

original geometric mosaic floor has survived. Here we see guilloche interwoven

squares that give life to eight-pointed stars which in turn create octagons. These

octagons are the visual high point of the floor and hold their own individual

design. Perhaps the most decorative is the open flower design as it prepares to

blossom. The spaces in between the interwoven squares have also produced eight

small white and black triangles. The remainder of the mosaic is filled by

squares and rhombic shapes which are visually supported by a dentil design.

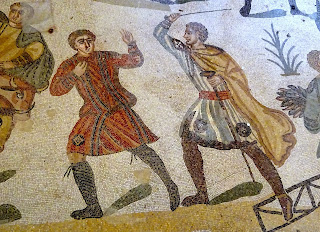

This rectangular room, close to the

service rooms, was assumed, due to the laying of a figurative mosaic, to

function as a bedroom for visiting guests. The depicted scenes are much damaged

while the lower part of this rooms’ walls reveal the remains of frescoes with

geometric designs.

This figurative mosaic is read as being a scene from Roman mythology which is known as The Rape of the Sabine Women. Early in the history of Rome, Romulus and his male entourage were seeking wives. They were consequently rebuffed by the inhabitants of the neighbouring villages and settlements. So slyly they organized a festival of Neptune (the Roman God of seas and water) and all were invited. During the festival, perhaps under the cover of darkness, many young women were spirited away to Rome. The myth ends by informing us that the women found happiness in Rome and refused to return to their homes.

This figurative mosaic is read as being a scene from Roman mythology which is known as The Rape of the Sabine Women. Early in the history of Rome, Romulus and his male entourage were seeking wives. They were consequently rebuffed by the inhabitants of the neighbouring villages and settlements. So slyly they organized a festival of Neptune (the Roman God of seas and water) and all were invited. During the festival, perhaps under the cover of darkness, many young women were spirited away to Rome. The myth ends by informing us that the women found happiness in Rome and refused to return to their homes.

What is left of this mosaic tantalizes my

imagination, for I feel that this scene transfers to me a sense of fear and

confusion. The woman on the top left hand side, frantically waves her scarf/veil,

desperate for help and hopes to attract somebody’s attention. On the far right

another woman leaning away to her right, struggles to ward off her abductor. At

the bottom left hand side a man looking back is presumably dragging away an

unseen woman, while next to him are the possible remains of a man sweeping up

and carrying away a woman. All of the characters portrayed in this mosaic are

smartly attired with designs shown on the shoulder pads, cuffs and bottoms of

the men’s tunics. Accessories also adorn the ladies. The one being carried away

seems to be wearing an ankle bracelet, while the one (top left) wears a double

row necklace.

A flood of disappointment wells up inside

of me for once again I have been denied from viewing a complete high class work

of art.

ROOM OF THE LOST MOSAIC (23)

This room was an antechamber serving as

an entryway into the main guest room as described above. Unfortunately its

mosaic floor has not survived. Also this area could have been utilised as a

waiting room if the person using the guest room was not yet ready to receive the

visitor.

ROOM

OF THE FOUR SEASONS (24)

This room’s main function was to be used as

an antechamber, probably by important visitors on official business or

alternatively by social family guests.

|

| MOSAIC BORDER |

The mosaic floor is exceptionally well

preserved and a geometric design, created with the use of diagonal lines from a

collection of rhombi and stars, is bound together by a spider web of guilloche.

All of the created hexagons have at their centre medallions some of which are

encased in a polychrome two pattern band of elongated right angles. Four of the

medallions feature busts representing the four seasons of the year.

They are

set in a background of off-white tesserae and enclosed within a black/grey

circle which helps to highlight their appearance. Spring seems to be of a

delicate young woman with roses in her hair, while summer is shown as a healthy

young man crowned with wheat ears. A woman whose hair is laced with grapes is

autumn and a man with a stern expression on his face with his head covered by

leaves and a warming cloak hanging from his left shoulder depicts winter. Some

of the remaining medallions show birds/fowl pecking at foliage and varying

species of swimming fish, while others display open flower designs encased in a

circle of pointed peaks and troughs. On the outer border we look down on a

fascinating and unusual tower and cube design.

If we look with a keen eye at the busts of

spring and autumn their faces, as do their clothes, seem extremely similar.

Also the face of summer smiles and he looks healthy and content, while with

winter the face is pensive and drawn.

This spacious square room is entered through

the room of the Four Seasons and assumed to have been furnished as a bedroom.

The room’s intricate and complex mosaic floor can have a mesmerizing effect on

our eyes but, if we can then engage our imagination to compose a composition of

the ceiling and match that to what is left of the frescoes, a high status

environment is before us.

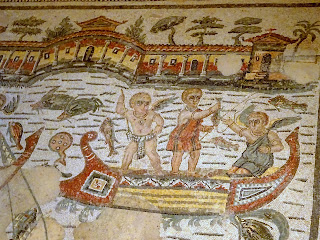

Joyously, most of this mosaic has survived

and its main theme is fishing, performed with the help of four richly decorated

small boats. Each of the vessels is manned by three fishermen depicted here by

cupids. (At Bignor Roman Villa there is a frieze of cupids dressed as

gladiators.) If we cast our eyes to just below the fishing boat at the top

right hand side of the mosaic, we see a naked cupid holding on to the rear of a

dolphin. It is well known that dolphins have an affinity to humans, so perhaps

what we are viewing here is the dolphins and the cupids working together. The

dolphins round up the fish into shoals to feed, while the cupids ‘muscle-in’ to

catch some for themselves.

The cupids in the fishing boats, top left

and bottom left, are fishing together by sharing a long net cast between their

vessels and are seen hauling in their catch. A cupid seen in the sea below the

top boat helps to drive the fish into the net. In the top right hand side a

cupid wearing a loin cloth is successfully spearing fish with the aid of a

harpoon. The one next to him is presumably fishing with a hoop net and then

passing the fish on to the third cupid who is seen reaching up with his right

hand to receive them. He would then pack the fish into a basket. In the boat

below a cupid is fishing with a rod and line, while the one to the far right is

releasing fish that have been caught by using a trap. The cupid bending down

packs them into a basket. All seem to be wearing decorative neck, arm and wrist

bands.

When the fishing ceased and with the catch

packed away, the boats made their way to the large imposing villa in the

background to unload. This activity could have taken place at the villa’s

exedra, the large semi-circular recess as noticed in the mosaic. If we now

remove our eyes from this splendid mosaic and look up at the lower parts of the

walls, stucco and frescoes are to be seen. The frescoes are of geometric design

with rectangular panels painted in red and yellow and contain what appears to

be the lower half of human figures. Unfortunately the rest has not survived.

This room is rectangular and is also located

in the northern part of the peristyle. It was probably another area available

for accommodating guests and used as their dining room, which could have been

supported by two service rooms close by. The thought has entered my mind that

considering hunting was a male pursuit, this could have been a gentlemen-only

room. A place where the proprietor of the villa and his male guests could have

pursued varying male pleasures.

This mosaic floor I believe was laid in

homage to Diana the Goddess of Hunting, whose festival of celebration was held

on the 13th of August. The setting of the villa was such that the

surrounding countryside would have inspired many of the hunting scenes that are

on view within this floor. The most significant part of the presentation is

just below a portrayal of two scenes of hunting dogs which show, on the left

hand side, two fierce looking dogs being controlled by a figure wearing a

yellow tunic. His compatriot on the right, holding a staff, has already

released his three dogs. Below them a statuette of the Goddess is displayed on

a tall base, high up between two trees. From here she looks down onto an altar

where she views offerings being made to her by a figure wearing a red tunic. In

his left hand he holds a plate, from which his right hand deposits meat onto

the smoking altar. If we return our eyes to the statue of Diana, we notice that

in her left hand she holds a bow and over her right shoulder is a quiver full

of arrows. Seemingly, her right hand is about to pull an arrow from the quiver.

To her left and right a wild boar and a hare/rabbit await their turn to be part

of the ceremony.

|

| THE MOSAIC BORDER |

Below, and perhaps after the hunting party

had finished paying their respects to the Goddess, they all relax on a circular

elongated cushion in readiness for a feast. A huge piece of meat has been set

before them on a round table supported by stones, while a slave offers up a

glass of wine and another delves into a basket. The man dressed in red takes

pride of place at the table and all of the hunters are protected from the sun

by a red canopy which has been hung between two trees. Close to the red canopy,

hanging from a branch in the tree, is a hunting net and at the bottom left of

this mosaic we are shown how it was used, for three stags in panic are chased

by two horsemen into the pegged-out net.

Other hunting activities are to be seen,

although, I believe, the most revealing and detailed creation is to be viewed

on the bottom right hand side. Once again the figure dressed in the red tunic

is most prominent. He is portrayed as the hero as he kills a huge muscular boar

with a spear and saves the life of a fellow hunting companion, who has been

floored by the beast which has gored his left thigh. The fierce hunting dogs

have failed to help as has the figure above, as he tries desperately to throw a

boulder on to the head of the rampant animal. The man next to him, in the green

tunic, cannot help for he looks perplexed and in a state of shock. In the

background is, possibly, a hunting lodge where the injured hunter may have been

taken.

The figure in red is without doubt the

most important person in this mosaic, a man of the highest rank and authority

and the owner of this villa. His hunting friends would have been individuals of

wealth and standing and it is possible that they financed this mosaic in

recognition and gratitude for his friendship and generosity.

The mosaic is encased by a flowing border

design of a double row of bells with central spindles in yellow. Beyond this

and held between off white tesserae is a surrounding double row band of black

tesserae. This in turn is framed by guilloche which is contained in a dentil

pattern. The walls still retain traces of frescoes and I find it difficult to

leave this mesmerising room for, as I retreat, I notice that all of the

characters have their feet and legs protected by sturdy boots and thick below-the-knee

stockings.

This area was probably a service

room used in relation to the guest rooms on the north side of the peristyle. It

holds a simple but eye-catching geometric design constructed with green, red

and black tesserae. All the circles are connected together, both top and

bottom, by shields with similar central motifs which then define octagons with

gentle concave sides.

A roaming guilloche binds the whole mosaic together, while inside the octagons rest laurel garlands. Within each garland there are circle motifs of stylised four or six petal flowers or crossed squares. On some parts of the mosaic a lack of available space allows only half of the central design to appear. The mosaic is bordered by a double flowing shallow arch design.

A roaming guilloche binds the whole mosaic together, while inside the octagons rest laurel garlands. Within each garland there are circle motifs of stylised four or six petal flowers or crossed squares. On some parts of the mosaic a lack of available space allows only half of the central design to appear. The mosaic is bordered by a double flowing shallow arch design.

This room is at the back of the previous one

and also serviced the close-by guest rooms. The mosaic is a multi-coloured

geometric chequerboard design divided in 5x5 squares. It is elegantly crafted

and supported by the mosaicist’s generous use of colour. Every second square

contains a design with a smaller square diagonally inserted. Outside these

smaller squares and in the four corners a pelta (a small shield) motif is seen.

The smaller diagonal squares hold a reddish wave pattern and within this are smaller third squares containing stylised flower motifs. Alternate squares are dressed with guilloche, which then surround an inner square. Beyond a double fillet of black tesserae, the inner third squares contain a petal flower design. Another holds a swastika and within its four arcs are individual motifs where the coloured designs are reversed. Unfortunately, many of the guilloche squares have lost their central motifs. The outer border of the mosaic is sympathetically coloured to tone in with the main design.

|

| THE BORDER OF THE OCTAGON MOSAIC |

|

| THE ENTRANCE BETWEEN THE TWO SERVICE ROOMS |

The smaller diagonal squares hold a reddish wave pattern and within this are smaller third squares containing stylised flower motifs. Alternate squares are dressed with guilloche, which then surround an inner square. Beyond a double fillet of black tesserae, the inner third squares contain a petal flower design. Another holds a swastika and within its four arcs are individual motifs where the coloured designs are reversed. Unfortunately, many of the guilloche squares have lost their central motifs. The outer border of the mosaic is sympathetically coloured to tone in with the main design.

The corridor of the great hunt is about 60 metres in length and leads to

the owner (Dominus) and his families’ suite of rooms. It bypasses the basilica

where more of the official business of the villa would have transpired. The

corridor has apses at both ends and is located between the peristyle to the

west and the basilica and private rooms to the east. A gallery of eight columns

with Corinthian capitals separate the corridor from the peristyle.

As I view this corridor I become

enchanted and slowly overwhelmed, for this mosaic is unique and unparalleled in

any known roman building yet discovered, not only for its astonishing length,

but for the beauty of its content and the story that it portrays.

Although in some areas the mosaic is damaged, it is surprisingly well

preserved and large parts are practically intact, although there has been some

subsidence along its southern part. It seems that the two apses are symbolic of

the eastern and western limits of the geographical map of the then known Roman

Empire which was populated by a wide variety of fierce and ferocious wild

beasts. The political and social structure of the Roman hierarchy, plus the

demands of the empire’s citizens for entertainment, sealed the fate for

hundreds and thousands of these magnificent and proud animals.

History tells us that the Roman Emperor Titus,

son of Vespasian, inaugurated the colosseum with a hundred days of spectacle in

which 5,000 wild animals were slaughtered. Other ambitious Roman politicians

would have tried to enhance their careers by putting on blood sports and wild

animal shows. Criminals would have suffered execution by being mauled to death.

Because of the vast amount of exotic

animals required, it would have created a lucrative cottage industry in the

Roman Provinces, stretching from the most distant parts both to the east and

west of the empire. It was a well organised operation administered by the Roman

military with the support of slaves and local hunters from the surrounding

villages. The hunt starts at both ends of the corridor, where there are images

of places at the extremes of the Roman Empire with Africa represented on the

left hand side.

Africa at this period in time had five Roman

Provinces. Mauritania (Western Africa), Numidia (north of the Sahara), Byzacena

(Tunisia), Tripolitania (Libya) and Proconsular Africa. The mosaic in the apse

is unfortunately damaged, although the remains of a female figure is noticed.

Perhaps she wears the national dress of one of the above provinces. Her outfit

is smartly embroidered and over her shoulder a shawl is held together by a

large expensive looking broach. Further down is a possible belt which is

decorated with a row of precious stones? Close by are the visible remains of a

brown bear and a panther.

Within the left hand side of this expressive

composition we view the capture of exotic wild animals from the five named

provinces. Noticed are lions, panthers/leopards wild horses, elegant antelopes

and boars. In the background is the African landscape showing numerous trees,

including palms, within a mixture of village houses and arcaded buildings.

Just

beneath the colourful border of the mosaic we see a soldier being forced to the

ground by a leopard/panther. The animal is leaking blood from a wound caused by

a spear. Next to that there is a leopard which has bounded on to the back of an

antelope. Moving on, a snarling beast which has killed an antelope looks back

at two approaching soldiers. The soldiers are depicted carrying protective

shields and wearing long cloaks. The figure on the left, with a swastika motif

visible on the bottom of his tunic, points in the direction of their struggling

comrade. In the context of the hunt the swastika (four-legged) could perhaps be

symbolic, drawing in good fortune from the north, east, south and west.

Prior to this, seemingly in a different province, set in a vast open plain environment with scrubland in the background, leopard hunters equipped with spears form an impenetrable wall with their shields. Another hunter tries to entice the beasts closer with an animal carcass. Presumably this results in the leopards being surrounded, restrained and captured with the use of nets. But, the figure in control of the bait may be ready to trigger a trapdoor as the beast grabs the meat; the leopard, consequently, falls into a deep pit.

Prior to this, seemingly in a different province, set in a vast open plain environment with scrubland in the background, leopard hunters equipped with spears form an impenetrable wall with their shields. Another hunter tries to entice the beasts closer with an animal carcass. Presumably this results in the leopards being surrounded, restrained and captured with the use of nets. But, the figure in control of the bait may be ready to trigger a trapdoor as the beast grabs the meat; the leopard, consequently, falls into a deep pit.

The complexity of this mosaic corridor is

dazzling. Lions are being stalked, wild horses are gathered up and below is a

scene where the captured animals are being transported in a cart drawn by two

oxen. A soldier helps by pushing the back of the cart, while another on

horseback supervises the operation. Finally we see the animals boarding a ship,

possibly at the port at Carthage, for in the background are buildings in the

classical style. Our eyes now begin to explore a busy and expressive scene as a

slave has engaged the wrath of a centurion. Two ostriches are assisted up the

ramp, following in the wake of a large antelope which has the attention of

three slaves. The sea seems calm and abounds with fish. Other slaves await

their turn to load their captured animals. A wild boar, trussed up in a red net

which is secured to a pole, is noticed, while behind them two more slaves share

the weight of a large box stabilised by a pole. On board the ship more slaves

oversee the loading procedure and, with a keen eye, the padlocks that keep the

animals secure in their cages can be seen. From here the live cargo would sail

to the port at Ostia and then on to Rome.

If we turn our eyes to the right hand side

of the ship we see the cargo being unloaded in Italy. This part of the central

scene is close to the entrance of the basilica where four smartly attired

slaves, wearing similar tunics, are unloading a large heavy box, as another

slave escorts an ostrich down the ramp.

Now we turn our attention more to the

right and look towards Egypt.

We

continue to view a never ending swirling mass of colourful movement and

activity, as a rhinoceros has fallen victim to the hunt. It is being dragged

out of the marshy swamp by the use of ropes. Being a beast of strength it has

the attention of five slaves. Three pull hard trying to remove it from its

sticky clinging environment, while the other two demonstrate encouragement.

Seen close by a hippopotamus is squelching in the mire.

Many animals are being led, pulled and

bullied towards the awaiting ship at the port at Alexandria. Noticed is a

muzzled muscular tiger, a graceful antelope, a buffalo and a protesting

elephant. Above are two men, one holds the reins of a horse while the other

controls, seemingly, an Arabian single hump camel. These camels would have

proven their worth as pack animals for the Roman military. Also to be viewed is

a scene of a lion hunt where one of the beasts has been speared by a lance and

attacks a soldier who has been forced to the ground.

|

| THE PERSONIFICATION OF INDIA |

Within the apse on the far right is a

personification of India. The dark skinned woman looks pensive and sad, as does

the tiger and elephant. The woman has long hair clinging to both shoulders that

is held in place by a silver band across the top of her head. Her forehead,

between her eyes, is decorated by a single downward line of red dye. Perhaps

she is of aristocratic birth for gold jewellery dresses her neck and arms. An

elephant tusk rests between her left hand and arm while, interestingly, her

right hand grips the near top of a spice tree and hanging from the branch,

beyond her left shoulder, are strips of coloured fabrics. I feel that this part

of the apse is symbolic in telling us that the Roman Empire, after the

establishment of Roman Egypt, initiated trade with India regarding spices,

silk/cloth and ivory along the ‘silk-road’ and Indian Ocean. Because of the

vast distance between India and Rome, to have imported exotic wild animals from

India would have perpetuated much expense and organization.

On the left hand side, above the

elephant, is the mythical bird the phoenix, which has thrown itself into the

flames of its burning nest only to be reborn from the smouldering ashes in the

near future. There are a range of interpretations regarding this action which

include the representation of the victory of life over death and therefore

immortality. The significance here could be that India itself would always be

immortal during this time in its history because of its ability to supply the

then known world with its many sought after luxuries.

|

| TIGRESS VIEWING HER REFLECTION |

Returning

to the main part of the corridor, two other scenes engage our imagination.

Noticed is a soldier galloping in haste up the gangplank of an awaiting ship.

Apparently he has stolen a number of tiger cubs and to distract the pursuing tigress

he has dropped a glass ball. We observe the tigress viewing her reflection in

the ball and, believing it to be one of her cubs, stops her pursuit to rescue

it, consequently her family is lost. To the rear of the desperate and

despairing tigress is a griffin, perched on a cage, seemingly attracted by a

forlorn human face, peering out from beyond the bars and witnessing the

unfolding collective endeavours of soldiers and their slaves. The griffin with

the body, tail and back legs of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle also

possessed talons as its front feet. It was recognised as the king of both

beasts and birds. The symbolism here is that the might of the Roman Empires

civilisation dominates all things including nature, for the griffin had become

a helpless spectator.

The skilful hands of the mosaicist portray the Roman Military as heroes, all are recognised by their red belts. Not only do they fight for the empire and keep Rome safe, they also put their lives at risk by stalking and capturing dangerous wild beasts for the civil population to enjoy the spectacle of the animals’ deaths in the Colosseum and other amphitheatres. But, of course, the operation regarding animal trafficking was far more sophisticated than what we see before us; injured and wounded animals would have probably been worthless. The truth is within this corridor; it is elusive, but subtly illustrated by the mosaicist. First we see the local hunters holding their protective shields as they capture leopards in a pit. Snaring animals in this way was popular and successful, as was the staking out of nets, while blazing torches would have been used to round-up the beasts and lure them into pits. The imperial army would possibly have helped with their capture in this manner rather than hunt them as seen in the corridor. Another revealing scene is located in the upper central part of the corridor where a group of three men have gathered. The middle figure seems to be the most visual for he wears a small round cap and holds out from his right hand a long rod which has a mushroom shaped handle. All three are probably from the military elite with the central figure being of senior rank and responsible for a smooth conclusion to the activities. It appears that all three are dressed in tunics with decorated cloaks tied over their right shoulders. Seemingly, at least, two of the cloaks are of ankle length and have a swastika pattern on the bottom. Perhaps the figure on the left held the responsibility to deal with the finance of paying the animal traffickers and the figure on the right was responsible for assigning the cargo to the various amphitheatres and arenas.

The skilful hands of the mosaicist portray the Roman Military as heroes, all are recognised by their red belts. Not only do they fight for the empire and keep Rome safe, they also put their lives at risk by stalking and capturing dangerous wild beasts for the civil population to enjoy the spectacle of the animals’ deaths in the Colosseum and other amphitheatres. But, of course, the operation regarding animal trafficking was far more sophisticated than what we see before us; injured and wounded animals would have probably been worthless. The truth is within this corridor; it is elusive, but subtly illustrated by the mosaicist. First we see the local hunters holding their protective shields as they capture leopards in a pit. Snaring animals in this way was popular and successful, as was the staking out of nets, while blazing torches would have been used to round-up the beasts and lure them into pits. The imperial army would possibly have helped with their capture in this manner rather than hunt them as seen in the corridor. Another revealing scene is located in the upper central part of the corridor where a group of three men have gathered. The middle figure seems to be the most visual for he wears a small round cap and holds out from his right hand a long rod which has a mushroom shaped handle. All three are probably from the military elite with the central figure being of senior rank and responsible for a smooth conclusion to the activities. It appears that all three are dressed in tunics with decorated cloaks tied over their right shoulders. Seemingly, at least, two of the cloaks are of ankle length and have a swastika pattern on the bottom. Perhaps the figure on the left held the responsibility to deal with the finance of paying the animal traffickers and the figure on the right was responsible for assigning the cargo to the various amphitheatres and arenas.

Further to the right and close to the bottom of the mosaic is another alluring scene. A richly attired bearded figure looks out upon the complexity of the hunt and he is seemingly protected by two soldiers bearing shields. He wears a flat cylindrical hat and in his right hand a staff is noticed. It has been suggested that he is the Emperor Maximian Heraclius. It is certainly possible that this villa was one of his ‘homes’ that he would have used within his realm, for it was worthy of such a man with its unbounded luxury and magnificence. Alternatively, this illustration could be of a local wealthy politically aspiring aristocrat whose money may be funding this hunt. His ambition would be to use some of the animals for public entertainment and boost his popularity. Whoever he may have been, having bodyguards suggests he was a person of some importance. Interestingly, on the shoulder of the bodyguard behind him a motif of an ivy leaf is noticeable. As ivy leaves are a recurring element within the mosaics at this villa, is this a silent and unsolvable clue?

Thick bands of off white and black tesserae

separate the mosaic from its main border which is topped by a double row of

black tesserae. But then, as I view below the black tesserae, I feel that my

eyes are becoming intoxicated by the rainbow of colours that are set before me.

And as I try to decipher its design, the more my mind is perplexed and then

seduced by its complexity. I cannot describe it, I can only stand, look down

and enjoy it.

This service room is located between the

peristyle and the room displaying the slender girls wearing bikinis. The walls

of this antechamber held panels framed by bands of yellow and red. At the base

of all of them was an individual band of yellow, while bands of both colours

rise up vertically from this base. One panel encases a stand-alone figure.

The floor is decorated with a geometric mosaic

which is bordered on its outside by bands of black and then white tesserae. A

single continuing strand of guilloche flows around the complete mosaic boosting

the visual impact and style of the border. The mosaic contains 66 squares which

are separated by vertical and horizontal white bands. Within these bands the

hands of the mosaicist have constructed smaller squares by using point to point

black triangles, laid alternately, which then create white squares. At the

centre of these a small white cross is noticed, formed by four small separate

triangles in black. A band of Z patterned right-angles enclose the motifs in

all of the large squares within the mosaic. Stylized flowers are seen formed by

the use of four triangles, as do spindles arranged like the petals of flowers.

Others contain poised squares which have central crosses.

THE ROOM OF THE BIKINI GIRLS (31)

This room is located between the

peristyle, the corridor of the great hunt and the hall of Orpheus. It is

entered from the peristyle and then through the antechamber. The room is

rectangular with an eye catching figured mosaic floor. When human eyes once

again fell upon this work of art, it was known as the chamber of the ten

maidens.

The mosaic presents to us ten, young,

slim and athletic looking women although much of one has been lost. Most are

engaged in Olympic style disciplines. Weight lifting, discus throwing and

running activities are noticed in the top half of the mosaic. In the bottom

half, and to the right, ball games are represented. The young athlete second

from the left is holding a spoked wheel; perhaps this was used in a contest of

skill which involved rolling it along the ground and controlling it with the

stick. This could have been a team game, or a race over a set distance with a

number of individual competitors. Possibly, these ladies’ sporting events were

held locally or within the villa grounds. The scene at the bottom is certainly

indicative that there was a competition of some sort. The maiden, first on the

left and draped in a golden gown, moves with hast to present the winning

athlete a rose crown and a palm leave. Would this room have been for ladies

only and perhaps their gymnasium?

On viewing the top five athletes again,

I notice that the one holding the discus seems to be wearing items of body

decorations around her neck, upper and lower arms and ankles. If these are

expensive pieces of jewellery, she may well be associated with the resident

family of the villa, perhaps a daughter.

In

the south east corner a small area of the original mosaic floor has been

revealed. It is of geometric design, which suggests, that this room was

formerly a service area. The mosaic would been a collection of large eight

pointed stars, each star formed by two intertwined squares. The guilloche within

them is of red and grey colours, as is the garland which contains a flower

motif at its centre. The border blends well with the mosaic, for that too is

also red and grey and perhaps we see squares in perspective at the top, and on

the side a row of tangent cuboids. The border for the later mosaic consists of

bands of alternating off-white and black tesserae supported by a row of tangent

isosceles triangles in black.

|

| MOSAIC REMAINS FROM BENEATH THE BIKINI GIRLS |

This rectangular room 10m x 8m, and perhaps a

small basilica, is located on the south side of the peristyle close to the

previous room. Two grand marble columns mark the entrance from the peristyle.

On entry, my eyes sweep hungrily around the room while my imagination tingles

with excitement.

Within the apse is the base for the statue

of Apollo, the mythological father of Orpheus. His marble torso, now on

display, was discovered during the excavations and subsequently returned to its

original location. Within the centre of the room is the basin of a square

shaped fountain. Its murmuring and gurgling would have enlivened this room,

which would have had the same soothing reaction on human ears as Orpheus had on

the animals, when playing his bewitching music on his lyre.

The musician, or what is left of him, sits

upon a stone under a tree that spreads out into the apse. Orpheus is clad in a

crimson cloak and is wearing what looks like red shoes. An inquisitive fox creeps

cautiously up close to him as the animals become enchanted by his melodies. It

seems that the larger animals are just arriving and close to the entrance of

the room we see a bear, horse, rhinoceroses, buffalo, lion and a tiger. The

smaller land animals seem to be in the centre of the room while the birds,

including a phoenix, are towards the apse.

Between the lizard and the camel is the

closed tail (train) of a peacock and the shadowy reflection of its elaborate

and iridescent eyespots is shown beneath it. The mosaicist finishes his

creation with a generous and continuing border of laurel wreaths.

|

| THE PHOENIX |

As this room could be entered from the

peristyle, it was probably open for public use as a peaceful and relaxing place

for leisure activities, including music.

This

connected the hall of the Big Game Hunt and the families’ private apartments

with the Triclinium. It would have been decorated with a mosaic threshold,

spiral columns and shrines. This court would have also permitted access to the

inner peristyle and xystus (a covered portico).

Close to the apsis of the xystus a corridor

connects the square shaped peristyle, from its south west corner, with the triclinium.

It is noticed that the threshold of the peristyle is decorated with a mosaic

cantharus with volutes of acanthus. The rest of the mosaic floor contained

volutes of small birds and the busts of larger animals such as tigers, bears

and horses. Invited guests would have used this corridor to access the

triclinium while the owner and his family would have entered via the small

court.

THE KITCHEN (35)

This room had a beaten earth floor with two small walls projecting from

the wall of the peristyle which could have formed a hearth. Here food could

have been prepared and cooked for receptions in the triclinium. The uncovered

area behind the xystus would have given access for the servants to both the

portico and the triclinium.

These three rooms possibly had duel

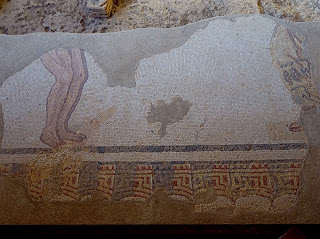

purposes, being service rooms and entertaining areas relating to the activities